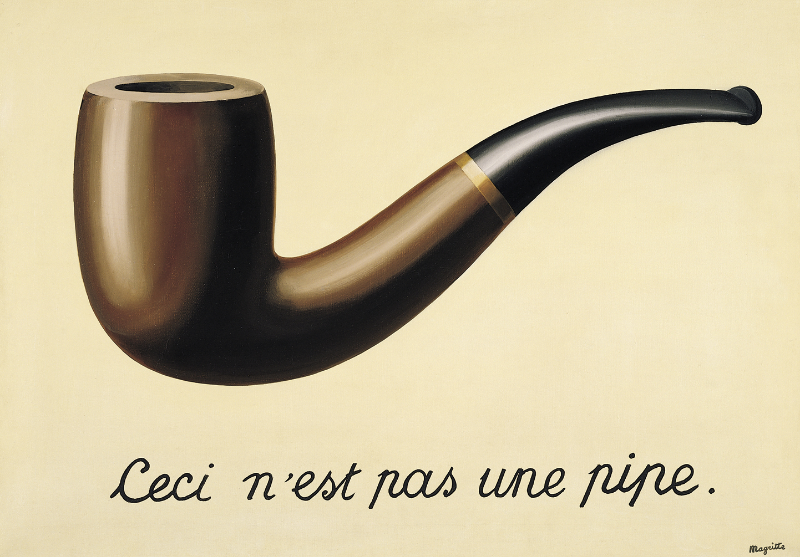

Rene Magritte, ‘La Trahison des images’, 1929

The Treachery of Images also known as ‘This Is Not a Pipe’ is what the creator of his famous painting called it.

‘Image’ because it represents a pipe. 'Treachery' because it is not a pipe.

This simple observation made this painting into an icon.

Rene Magritte (1898 – 1967) was a Belgian painter who occupied himself with essential questions surrounding our thought processes. He specifically studied thought processes which relied on observation and less those which started as a concept.

He, himself, tried to think and observe as if no one had gone before.

He reflected those things escaped our observation despite standing right in front of us.

We see what we want to see, or that which our mind reflects.

Or, freely translated by Paul Nouge, (Belgian poet and theorist – 1895 1967);

The eye sees thing that are no longer there, like a star in the heavens. Or the afterimage on a screen of something which has gone. The eye cannot observe very fast movements; a fired bullet from a gun, a fleeting smile. Likewise, it cannot detect very slow movements like the growing grass, or aging, or thinking that it recognises a familiar face when it turns out to be wrong. Or the image of a cat which turns out to be a shoe. Or apparent love which is not present.

The eye is free to interpret and jumps from significance to significance.

The search for meaning is an understandable way of getting a foothold on reality, if not the world. Besides that, it’s a handy tool to collect one’s thoughts without having to sift through the day’s observations one by one. However, it pays to be aware of these stereotype habits of the mind and question them as Magritte gladly did. He strived to make thought visible, thought through observation. This he undertook by using the same method: observation.

It is for this reason that Magritte worked with realistically painted objects and images taken from daily life; this was what mattered. The spectator knows the everyday objects which are painted on canvas before him. The epiphany is not that familiar bonds are missing. Something unexpected happens; an evening literally breaks down under a window, while outside the sun sets in the same view. Or things disappear, float, or burn without cause. Impossible! The representations are not possible. A mystery. And at the same time exactly as they are. Magritte painted with the purpose in mind to conjure up a mega reality that would surpass our understanding of the observable. Surpass because the invisible became visible. Yet the mystery remained the same.

Magritte considered his work a success when no explanation, no cause or consequence, could satisfy our curiosity. He shows us things and events without the tools we use to make sense of the world that surrounds us. The tools are there and appear in the apparent symbolism of the image but are in the end useless.

To paint things ‘as they are’ in paintings that ‘are as they are’ kept the mystery alive for Magritte. In his paintings the visible and invisible do not dominate each other. The coexist side by side and intermingle. The letter hidden inside the envelope is visible. The sun behind the trees just the same. In principal the mind yearns for the unknown. It thrives on a mystery, because it is, itself, a mystery. Why are we here? How do we know what we know? How can we possibly think that we can’t imagine our existence? We think using the invisible. A true mystery can be explained in many ways, but it will never be self-explanatory. This according to Magritte.

Conclusion: It’s the unexpected in Magritte’s work that provides the necessary information we seek. On its own. As phenomenon. Because our expectations are not met by the evidence. When someone mentions that the sun will rise tomorrow it’s nothing new. It’s self-evident. Of course the sun rises every morning. But what if something untoward happens straight in front of us on a canvas and at the same time in our mind, then there’s a sudden short revival. We notice something we know, but it’s impossible. Reality denies the impossibility that the canvas depicts, but in such a manner that it stays with the realms of possibility.

In many ways as dragons can be seen in a formation of clouds, which are not there. The clouds are there, the dragon is there; you see him, but know it’s impossible. Yet the clouds are there. The mind seeks and finds, recognises and denies, as an earth seems to orbit the sun, stars appear you can’t see, and strange shadows are cast over the moon’s surface, and then you’re not even dreaming yet…

‘Het verraad van de voorstelling’, zo noemde de maker zijn beroemd geworden schilderij.

‘Voorstelling’, omdat hier een pijp wordt voorgesteld. En ‘verraad’ omdat het geen pijp is.

Je kunt hem niet aansteken. Het is dus geen pijp. Deze in feite heel voor de hand liggende constatering maakte het schilderij tot een icoon.

Rene Magritte (1898-1967) was een Belgisch schilder die zich bezighield met wezenlijke vragen rondom ons denken, en dan specifiek het denken door de waar-neming, niet het denken vanuit een idee. Zelf probeerde hij te denken, en waar te nemen, alsof niemand hem daarin voor-gegaan was.

He reflected those things escaped our observation despite standing right in front of us.

We see what we want to see, or that which our mind reflects.

Or, freely translated by Paul Nouge, (Belgian poet and theorist – 1895 1967);

The eye sees thing that are no longer there, like a star in the heavens. Or the afterimage on a screen of something which has gone. The eye cannot observe very fast movements; a fired bullet from a gun, a fleeting smile. Likewise, it cannot detect very slow movements like the growing grass, or aging, or thinking that it recognises a familiar face when it turns out to be wrong. Or the image of a cat which turns out to be a shoe. Or apparent love which is not present.

The eye is free to interpret and jumps from significance to significance.

Dit zoeken naar een betekenis is een heel begrijpelijk streven om wat houvast te vinden in de wereld, en buiten dat een handig stuk denkgereedschap zodat niet de hele dag door alle waargenomen wielen weer opnieuw uitgevonden moeten worden.

Toch kan het ook van belang zijn dit te doorzien en deze stereotype gewoontes van de geest te bevragen, zoals Magritte graag deed. Hij streefde ernaar om het denken zelf zichtbaar te maken, het denken door de waarneming. En dit deed hij door hetzelfde middel te gebruiken: de waarneming.

Niet voor niets werkte Magritte met heel realistisch geschilderde voorwerpen en voorstellingen uit het dagelijks leven om ons heen; hier ging het om. De beschouwer kent de alledaagse objecten die voor hem op het schilderij te zien zijn. De openbaring schuilt er echter in dat het bekende verband ontbreekt. Er gebeurt iets onverwachts; een avond valt letterlijk kapot onder een raam, terwijl buiten de zon ondergaat in hetzelfde uitzicht. Of dingen verdwijnen, en zweven, of branden zonder reden. Onmogelijk. De voorstellingen zijn onmogelijk. Een mysterie. En tegelijkertijd precies zoals ze zijn. Magritte schilderde met het doel een meta-realiteit op te roepen die ons begrip van de waarneem-bare zou overtreffen. Overtreffen omdat ook het onzichtbare zichtbaar werd. En het mysterie onverminderd aanwezig bleef.

Magritte considered his work a success when no explanation, no cause or consequence, could satisfy our curiosity. He shows us things and events without the tools we use to make sense of the world that surrounds us. The tools are there and appear in the apparent symbolism of the image but are in the end useless.

De dingen ‘schilderen zoals ze zijn’ in schilderijen die ‘zijn zoals ze zijn’, hield voor Magritte vooral in dat het mysterie bleef bestaan. In zijn schilderijen overheersen het zichtbare en het onzichtbare elkaar niet. Ze bestaan naast elkaar, en door elkaar heen. De brief die in de envelop verscholen zit is zichtbaar. De zon achter de bomen net zo goed.

De geest heeft in principe een hang naar het ongekende. Het voelt zich thuis bij het mysterie, omdat het in zichzelf ook een mysterie is. Waarom zijn we hier? Hoe weten we wat we weten? En hoe kunnen we denken dat we ons niet kunnen voorstellen dat we daadwerkelijk bestaan? We denken met het onzichtbare. Een werkelijk mysterie kan op vele manieren verklaard worden, maar het zal nooit zichzelf verklaren.

Volgens Magritte.

Conclusion: It’s the unexpected in Magritte’s work that provides the necessary information we seek. On its own. As phenomenon. Because our expectations are not met by the evidence. When someone mentions that the sun will rise tomorrow it’s nothing new. It’s self-evident. Of course the sun rises every morning. But what if something untoward happens straight in front of us on a canvas and at the same time in our mind, then there’s a sudden short revival. We notice something we know, but it’s impossible. Reality denies the impossibility that the canvas depicts, but in such a manner that it stays with the realms of possibility.

In many ways as dragons can be seen in a formation of clouds, which are not there. The clouds are there, the dragon is there; you see him, but know it’s impossible. Yet the clouds are there. The mind seeks and finds, recognises and denies, as an earth seems to orbit the sun, stars appear you can’t see, and strange shadows are cast over the moon’s surface, and then you’re not even dreaming yet…

“Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish;

A vapour sometimes like a bear or lion,

A tower’d citadel, a pendent rock,

A forked mountain, or blue promontory

With trees upon ’t, that nod unto the world,

And mock our eyes with air..”

Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra

“Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish;

A vapour sometimes like a bear or lion,

A tower’d citadel, a pendent rock,

A forked mountain, or blue promontory

With trees upon ’t, that nod unto the world,

And mock our eyes with air..”

Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra